I’ve never been to a revival in the deep south, but I imagine the sweat is a part of it. I imagine you’re on your feet for too many hours but don’t notice. People are not just joyful, they’re elated. Not just singing, but worshipping. And they are not just witnesses. They’re believers.

The night I spent at the Eras Tour concert with my daughter, in celebration of her 21st birthday last year, was as close as I’ve come to that sort of spiritual experience. It wasn’t the deep south, it was Nashville, but the air was so heavy with damp, it might as well have been. There was no pastor on stage, but there was Taylor Swift. And there was no bible being read; we had memorized the entire canon.

To be frank, I’ve never been a Swiftie, but I accidentally raised one. I myself am perpetually committed to Sad Songs™ usually warbled out by a man with an acoustic guitar and wavy hair that looks unwashed. But my daughter was choreographing hand motions to Taylor’s songs by first grade. Using hand motions, as she’d learned in Sunday School, was the way to show you really believed the lyrics. Moving your body to the music in a sort of interpretive way meant you were singing with not simply your voice, but your soul.

As all the faithful do, she has evangelized me over the years, sharing her enthusiasm for this song or that album, and I offer this confession: I never quite felt the spirit descend. But then came the pandemic, and Taylor got sad, and I started listening. I know, I know. Those of us who started showing up at Folklore are not purists. We don’t know the lore and maybe don’t deserve to speak on the old magic, but that’s the whole thing of it. Swiftie love proves unconditional; no matter when you knock at the door, it opens unto you.

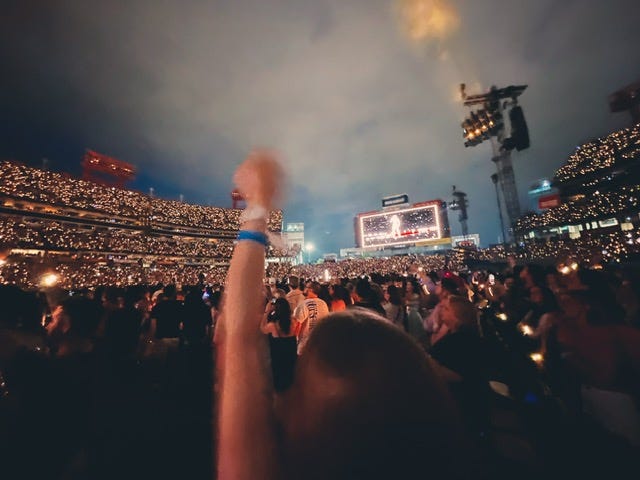

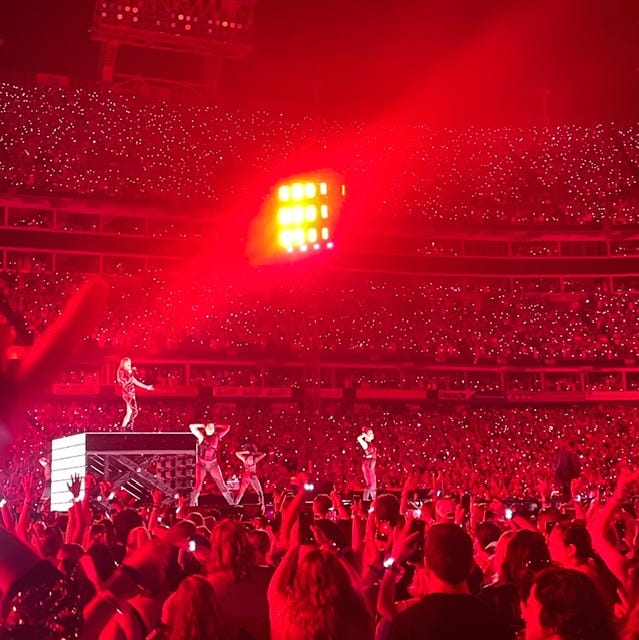

The night when my daughter and I and 70,000 more gathered under a full moon for six hours must be discussed. I’ve been to a lot of concerts. Growing up in the Los Angeles suburbs meant I had fairly easy access to every genre of music, every size of venue, and every night of the year to hear live music. My concert attendance started around age 12, and my love for a live show has only ever deepened. But the Eras Tour was unlike any I’ve attended. It’s not uncommon for concerts to feel spiritual; I’ve been moved by my favorite songs belted out into the night sky at the Hollywood Bowl, or whispered right over our heads in hazy, intimate venues off Sunset Boulevard. This night was different. Halfway through, I scanned the sea of bodies chanting in unison, folks not only knowing every word to a song, but anticipating every inflection, every subtle movement of the music. The unity, the pure cohesion among the throngs was remarkable, and I thought in that moment, Churches would kill to have fellowship like this.

I started asking myself, what is it, exactly, that brought this many people together, bound by such passion and loyalty? Why did it feel so unlike any concert experience I’ve ever had? And why did it feel holy? I should also tell you I’ve spent over forty years sitting in pews on Sundays. I wasn’t simply a regular churchgoer. I didn’t skip. Couple that with holding leadership roles in churches and parachurch orgs since I was a teenager, I’ve seen the inside, the outside, the backrooms, the boardrooms, the baptismals, the basketball gyms, the prayer chapels, the cry rooms, the summer camps, the dining halls, the kids’ clubs, the Bible studies, the singles clubs, the marriage classes, the moms’ clubs, the women’s retreats, the brunches, the potlucks, and everything else in between. If it happens in a western evangelical church, I’ve probably attended it or coordinated it. Sometimes led it. So, I can say from experience, the Taylor Swift concert fed its flock like the best of them. Maybe better.

Back to the sweat. That night was perhaps the stickiest I’ve ever been. You can see our faces glistening in the photos. The heavy heat clung to our bodies as we danced and sang without stopping, and something was happening. You’ve probably already heard about the outfits (more sequins than you’ve ever seen), the friendship bracelets stacked up nearly every wrist, and the irresistible camaraderie. Everyone made friends with everyone in their seat vicinities. But there was something else, something even more holy than the palpable emotional safety, personal expression, and joy. Each of us heard our song, each of us had our humanity named and honored.

Someone heard their melody of a love so good it hurts. Someone heard their anthem of rage after being betrayed and replaced. Someone heard their story of being made to feel powerless. Someone knew that Taylor knew how heartbroken she was when the one person who mattered most didn’t show up. Someone nodded at how many memories can be trapped inside a piece of clothing. Someone teared up when they heard their story. Someone wept. I heard mine, a story of being tolerated instead of treasured. And then, my story of wishing for justice, and then, my story of what it feels like to wear red lipstick. And be an ex-wife.

Churches at their best name people and their stories in a way that heals our wounds and softens our self-protecting hearts, safely drawing us toward the possibility there exists a divine being who might just love us as we are. This is why buckets of guilt, shame, and fear being passed down the pews doesn’t work as an entry point to faith, and why improperly naming us Wicked or Broken is, at the least, confusing. At the worst, it’s traumatizing. In contrast, Taylor Swift is simply a songwriter, and her art is simply a vehicle for some potent messages that we are seen and known, we are in safe community, and we are going to be okay.

I don’t think it’s over-spiritualizing to say all of this rings with our truest name, Beloved. I’m sure some might argue I’m being a bit dramatic to say that Taylor Swift’s music consistently names us the Beloved of God, but I’d argue right back. Look at the fruit of the work; there was a concentrated goodness at the show that I didn’t expect and hadn’t experienced before. Even if you haven’t personally witnessed it, the theory does explain the sheer power of her brand. It’s because she is not building a brand, she’s building a fellowship.

The exponential, global expansion of this fellowship has been extremely successful not because her followers are “of the world” or deceived. It’s certainly not because they see Taylor as a god to be worshipped. It’s because her community pours out something genuinely life-giving, something that reminds us of our sameness and of our unshakable goodness. Many of us went to church for these things and did not find them. Of course, it’s not Taylor Swift who sees and knows us, but the Eras Tour concert powerfully reminds us that we are surrounded by a great cloud of witnesses. We are seen and known by one another when we worship together, hands raised in praise of our own survival. We have been through some brutal shit. We have the scars and the receipts. And we will heal side by side. There is safety in numbers.

One definition of prophet is someone who communicates the heart of God to people, who takes divine truth and translates it into meaningful and accessible language to minister to the hearts of anyone who is willing to listen. Sometimes the messages are warnings and other times they are encouragements. Sometimes the point is just to let us know we are not alone. In that regard, I often see a prophetic gift in an influencer or celebrity or the beaming clerk stacking tomatoes at the grocery store who chats with everyone and hugged me once. It’s not at all a stretch to notice ways in which Taylor is passing out blessing, one swelling-in-your-chest bridge at a time. We are so desperate to be seen. We are so afraid that we are alone in the dark. And when I’m listening, what I hear her saying, again and again, is You are beautiful. You are worthy of love and belonging. You are the Beloved.

I tend to agree.

You are the Beloved,

Leslie

One caveat that I want to address as a footnote: Taylor Swift’s “fellowship” is accessible only with certain types of privilege and I want to acknowledge that is where my metaphor breaks down. You could argue the same is true in most churches. But to clarify, this piece is more a conversation about why her appeal is so vast, and not how her brand, and particularly her concerts, are certainly exclusionary.

This is SPECTACULAR. ✨

(and glad you added the disclaimer - two things true at the same time. 🩷)